Patients who present with corneal inflammation can pose a diagnostic challenge for the ophthalmologist, as the inflammation may be confined to the eye or, alternatively, may be a manifestation of an underlying, potentially life-threatening systemic infectious or inflammatory disease, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Such diseases may result in possibly sight-threatening inflammation in and around the eye. (See “Corneal Inflammation: An Overview”.) Although corneal inflammation, or keratitis, may present in patients who have a long-standing history of a systemic disorder, the inflammation may also be the initial presenting sign of a new systemic disease.

With this in mind, this article discusses the diagnosis and treatment of corneal inflammatory manifestations associated with systemic disease.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of a corneal condition linked with systemic disease is comprised of the following action steps:

• Obtaining a comprehensive patient history. A comprehensive history is comprised of family history, past medical and surgical histories, including medications and allergies, social history (including occupation and travel), and review of systems.

A detailed ocular history is made up of ocular medications and surgeries, history of infection and contact lens wear, and onset and duration of symptoms. A questionnaire can be useful in efficiently and thoroughly assessing patient history.

• Assessing clinical symptoms and signs. Ocular symptoms associated with systemic disease may range from mild to severe, depending on the level of inflammation, and typically involve redness, irritation, pain, tearing, blurry vision, photophobia, and periocular pain.

Using the slit lamp, we should examine the eye from front to back to ensure nothing is missed. The lids may harbor lesions, such as molluscum contagiosum, that can affect the cornea. The bulbar and palpebral conjunctiva should both be examined for injection, papillae or follicles or by staining with dyes. Conjunctival cicatricial changes can point to underlying conditions, such as mucous membrane pemphigoid or atopic keratoconjunctivitis. Conjunctival biopsy is a useful tool to confirm the diagnosis of mucous membrane pemphigoid and may also be helpful in patients who have granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), formerly known as Wegener’s granulomatosis, where biopsy of other involved organs may be contraindicated. Episcleritis may be distinguished from true scleritis by room light and slit lamp exam, mobility of episcleral nodules with a cotton tip applicator, and by blanching with phenylephrine drops. Scleritis will exhibit a classic violaceous hue due to engorgement of deeper scleral vessels via slit lamp.

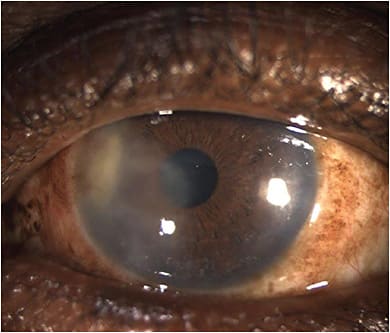

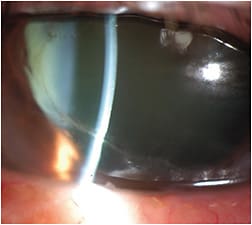

We should examine the cornea closely to localize the inflammation. Superficial inflammation may result in punctate keratopathy, a non-specific finding. The most common corneal manifestation of systemic autoimmune disease is keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS). Schirmer’s testing may be useful to confirm the degree of severity of KCS. Corneal sensation testing can indicate a neurotrophic component to the ocular surface disease. Classic dendritic or dendritiform keratitis may point to a herpetic origin. Subepithelial infiltrates may be inflammatory sequelae of viral or bacterial infections, such as adenoviral or herpetic keratoconjunctivitis or Lyme disease. Interstitial keratitis, defined as isolated stromal inflammation and neovascularization without ulceration, may point to a variety of infectious or inflammatory etiologies, such as herpes simplex virus (HSV) (Figure 1), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), syphilis, tuberculosis, or sarcoidosis. Endotheliitis with keratic precipitates is also suggestive of a viral disorder, such as HSV or cytomegalovirus. Anterior uveitis may be isolated or secondary to corneal or scleral pathology. Iris transillumination disorders that are sectoral or diffuse may suggest a herpetic origin. Lenticular changes may also give us clues: Anterior subcapsular cataracts may be seen in atopic patients, while posterior subcapsular cataracts in the absence of frequent topical steroid use may indicate previous intraocular inflammation.

Corneal ulceration may be due to inflammatory or infectious causes, and the position in the cornea may be suggestive of the underlying cause:.Peripheral corneal infiltrates and ulcerative keratitis (PUK), in particular, often are associated with autoimmune connective tissue disorders, most commonly rheumatoid arthritis (RA) (Figure 2). Other causes of PUK include GPA, SLE, polyarteritis nodosa, and relapsing polychondritis. Rosacea may also be associated with peripheral ulcerative changes and neovascularization. Mooren’s ulcer is a diagnosis of exclusion in patients who have PUK. A static, non-healing epithelial defect suggests a neurotrophic etiology, while suppurative keratitis can be secondary to a variety of infectious etiologies. Central or paracentral corneal melting without stromal infiltration may be indicative of primary or secondary Sjögren’s syndrome and may require rapid intervention to prevent corneal perforation.

• Acquiring a full dilated funduscopic examination. This should be performed to rule out other signs of inflammation, such as retinal vasculitis, optic neuritis, and vitritis. A brief neurologic examination to assess extraocular motility and pupillary response is also helpful in assessing certain vasculitic or neurologic disorders, such as Behçet’s disease.

• Performing an external exam. Based on clinical history, a brief examination of skin and joints may be helpful in assessing the character of arthritis and rashes. Examination of facial and periocular skin may reveal such inflammatory conditions as atopic dermatitis or rosacea, which may play a role in the underlying etiology of the ocular disorder. This patient should be asked about a history of rashes in other parts of the body, as well. Sometimes, for example, these rashes may actually be vasculitic in origin and require biopsy for confirmation. In these cases, our dermatology and rheumatology colleagues can be of assistance in helping to determine the underlying diagnosis.

CORNEAL INFLAMMATION: AN OVERVIEW

Corneal inflammation may result from either infectious or inflammatory etiologies. Systemic infectious etiologies include viral infections, such as HSV or VZV, and bacterial causes, such as tuberculosis and Lyme disease.

Inflammatory etiologies include autoimmune connective tissue disorders, such as RA and SLE; allergic conditions; specific granulomatous diseases, such as sarcoidosis; primary vasculitides, such as polyarteritis nodosa; or GPA; and autoimmune disorders of the skin and mucous membranes, such as mucous membrane pemphigoid.

Autoimmune disorders affecting the lacrimal system, such as primary Sjögren’s syndrome or Graft-versus-host disease, may also cause sight-threatening inflammation.

• Obtaining additional testing, when indicated. Laboratory testing should not be routinely used to screen patients who have ocular inflammation, although certain tests may have relatively high value. For example, all patients who have idiopathic uveitis are typically screened for syphilis using treponemal antibody testing.

Rheumatologic testing is useful in the confirmation of suspected autoimmune diseases based on medical history. In patients who have PUK or scleritis, laboratory testing for autoimmune diseases is particularly important, as these entities may signal the onset of life-threatening vasculitis.

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) are acute-phase proteins that can be elevated in response to an inflammatory response, but ESR can be elevated in some conditions as well, such as pregnancy and cancer.

Rheumatoid factor and anticitrullinated peptide antibodies (ANCA) are autoantibodies present in most patients who have RA. Antibodies to nuclear antigens include antibodies to Smith (Sm) antigen, Scl-70, ribonucleoproteins, Ro/SSA, La/SSb, PM1, and histidyl-tRNA synthetase, among others. These tests are useful in confirming the diagnoses of specific rheumatologic conditions, including Sjögren’s syndrome and SLE.

The ANCA test, particularly with the cytoplasmic pattern of staining (cANCA), is both sensitive and specific for GPA.

Complete blood count may be abnormal in infection or malignancy. Other more specific tests, such as QuantiFERON-TB testing for tuberculosis, Lyme, or viral (HSV, herpes varicella zoster virus, EBV) serologies, and angiotensin-converting enzyme and lysozyme for sarcoidosis, are performed when these entities are suggested by medical history and physical examination.

Chest radiography is indicated in patients whose ocular inflammation may be secondary to diseases involving the lungs, such as tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, or systemic vasculitis. Chest CT scanning may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis of sarcoidosis. Urinalysis may indicate renal involvement in patients who have inflammatory diseases, while routine liver and kidney function tests may also help outline the extent of disease and guide treatment planning.

We should always perform a corneal scraping in patients who present with corneal ulceration (with or without corneal infiltrates) to rule out primary or secondary infections. (See articles on pps. 14 and 18.)

• Employing corneal imaging. Corneal imaging, such as AS-OCT and in vivo confocal microscopy, may help delineate the involvement of the corneal inflammation. In vivo confocal microscopy is particularly useful in certain cases of infectious keratitis or in neurotrophic disorders.

Treatment

Treatment of corneal inflammation secondary to systemic disease is guided by the severity of the condition and the underlying diagnosis:

• Infectious disease. Patients who have infectious diseases, such as HSV or Lyme disease, require treatment for the underlying infection, as well as anti-inflammatory medications, such as topical corticosteroids, to address the inflammatory component of the keratitis.

• KCS. These patients should be managed with topical anti-inflammatory agents, such as cyclosporine (Restasis [Allergan/AbbVie] or Cequa [Sun Ophthalmics]), and lifitegrast (Xiidra, Novartis), as well as topical steroids, autologous serum tears, punctal occlusion, and other measures, such as tarsorrhaphy, and moisture chamber goggles to support the ocular surface. In addition to these measures, cenegermin-bkbj (Oxervate, Dompé), or recombinant human nerve growth factor, have been found effective in treating patients who have neurotrophic keratitis.

• Atopic disease. Patients who have atopic disease should be referred to allergy and dermatology specialists for testing to identify allergic triggers. Topical antihistamine and mast cell-stabilizing medications, topical cyclosporine and corticosteroid therapy, and avoidance of known allergens are typically beneficial. Oral cyclosporine and corticosteroids may be necessary in severe cases. Rosacea patients may also benefit from referral to dermatology specialists for management of their skin condition. In-office procedures, such as intense pulse light therapy, may reduce periocular inflammation and secondarily improve ocular symptoms.

Patients who have active ocular cicatricial pemphigoid, a subset of mucous membrane pemphigoid, often require systemic immunosuppressant therapy to control ocular inflammation and prevent progressive cicatrization of the ocular surface. In recalcitrant cases, the combination of intravenous immunoglobulin therapy combined with rituximab, a monoclonal antibody directed against the CD20 protein in B cells, has been shown effective in arresting disease progression and preventing blindness.

In cases of rapid corneal melting or perforation, cyanoacrylate glue and a bandage contact lens with topical antibiotics are utilized acutely to stabilize the eye, and corneal transplantation may be required later. More severe corneal melting may require emergent therapeutic keratoplasty for tectonic support.

• Autoimmune disease. Patients who have autoimmune diseases, such as RA or SLE, will usually require immunosuppressive therapy in cases of PUK and scleritis, as these conditions signal more serious disease. These agents require regular monitoring and are typically prescribed in collaboration with rheumatology and internal medicine specialists.

Acute suppression of inflammation often requires high-dose systemic corticosteroids, as immunosuppressive agents may take up to several months to become fully effective. Methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil (CellCept, Genentech), azathioprine, oral cyclosporine-A, chlorambucil, and cyclophosphamide have all been used successfully to treat PUK and scleritis, as well as other forms of ocular inflammation. The TNF-alpha inhibitors infliximab and adalimumab (Humira, AbbVie) have been used to treat PUK associated with a variety of underlying etiologies. Rituximab has been used successfully to treat a variety of refractory scleritis and PUK patients, particularly with GPA and RA. CP